To fully understand this, it seems necessary to make a clear distinction between the quantitative easing policy of central banks consisting of massively supplying banks and markets with “liquidity”, to be more precise in the money of issuing institutions, prolonging and broadening their historical action of last resort, and that consisting of the purchase of assets on the financial markets, public and private bonds, or even stocks. These two ways of conducting a QE policy induce the same inflation of the assets and liabilities of central banks, but by different means. In the first case the monetary authorities lend to banks, in very unusual circumstances, in order to avoid a liquidity shortage in the banking system. In the second, in equally unusual circumstances they buy assets from non-banking agents who, by selling them to central banks, receive money that they deposit in the banks; the latter thus ultimately holding more central bank money in their accounts with issuing institutions. We could call the first a policy of the liabilities of the balance sheet of central banks and the second an asset policy.

But the most fundamental distinction lies in the circumstances leading to the use of these policies. In the United States, as in Europe for example, they were initially used to deal with the very serious financial and economic crisis of 2008-2009. The risk of a chain of bank failures, as well as market dislocation, required breaking these catastrophic dynamics by temporarily suspending the logic of the financial markets and the contagious distrust between the banks themselves. Which could also have led to a destructive crisis of confidence among households in their own banks. Thus, the central banks increased their balance sheets to provide the banks with the necessary liquidity. De facto, with the interbank market frozen, they interposed their balance sheets even in the exchanges of liquidity between banks. Banks with excess liquidity no longer lent to other banks and kept their central bank money in deposits at the central bank, with the issuing institution itself then lending to banks requiring liquidity. This operation of credit thus adds liquidity in the banking system and inflates the Central Bank’s balance sheet. This is how central banks were once again the lenders of last resort to the financial system from 2008. But it was also in 2008 that the Fed decided to buy “toxic” assets to prevent the loss of confidence and bankruptcy of those who held them. And also to prevent the collapse of the price of these assets, the consequences of which would have been potentially disastrous for the economy. This is how central banks were able to curb the systemic risk that was developing

very quickly and which would otherwise have led to catastrophic economic and social consequences. The same was true around March 2020, during the very severe financial flash crisis due to COVID and lockdowns. Central banks then bought many assets, including high yield assets, particularly from non-banking financial institutions, including troubled investment funds, which made it possible to very quickly extinguish the fire that was suddenly taking hold.

Quantitative easing was then used and perpetuated with a completely different objective. The violent financial crisis was over, and as a result, the economy was very slow and inflation was at extremely low levels. With interest rates close to their effective lower bound, the weapon of key interest rates in conventional policy had become ineffective. This is why central banks began to buy financial assets to stimulate the economy and try to raise inflation. Then in 2020, with the economic consequences of the pandemic and lockdowns, they did the same. They have notably bought public debt bonds, in order to support the government’s very important fiscal efforts.

The effectiveness of this policy may come from the very announcement of the implementation of such a decision. The OMT program, for example, announced in 2012, led to a rebound in confidence following its presentation, even though it was never implemented. But its effectiveness may also come, of course, from the possibility it offers central banks to take control of long-term interest rates and risk premiums, or at least to substantially influence them. In this way, they can encourage households and businesses to invest, or even consume, more, in particular by lowering the cost of their loans. Credit, and its twin, debt, have also gradually recovered since around 2017 in Europe. The third transmission channel was the wealth effect triggered as a result of the fall in long-term rates on the value of stocks as well as on real estate. This wealth effect has thus supported demand.

Let us stress, however, that such a policy of quantitative easing outside of a situation of financial stress, to be effective, that is to say to stimulate the economy, must require central banks to buy much more assets, that is to say to create much more central bank money, than during financial crises. However, even if it requires injecting even more liquidity to reinvigorate economic growth as well as credit growth, this policy of purchasing assets has been useful. It has notably prevented a triggering of a deflationist cycle.

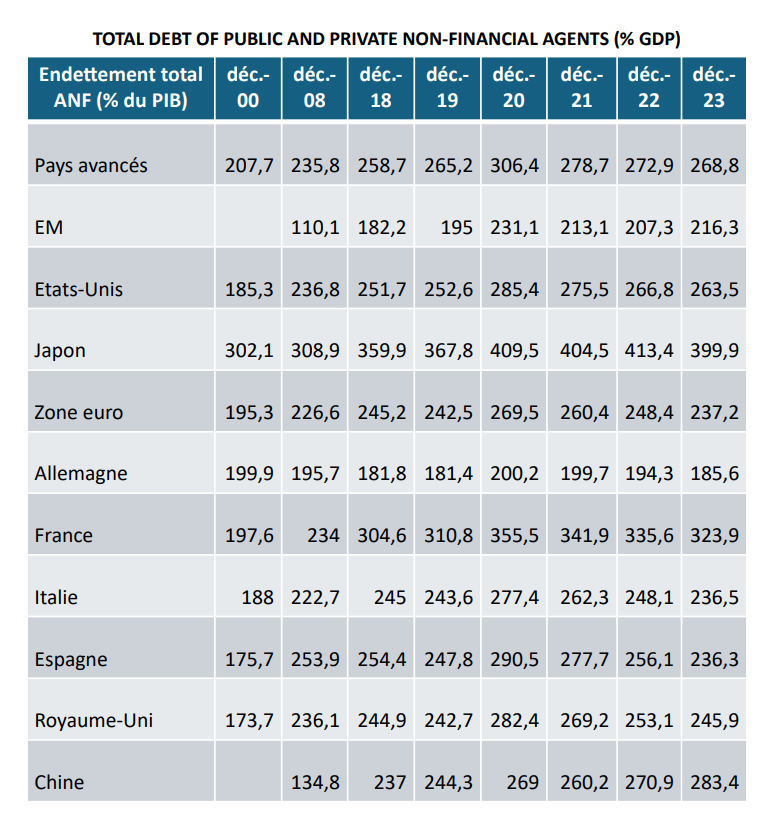

However, it failed to raise inflation. It is likely that the 2% inflation target did not correspond to a rate that met the contemporary mode of economic regulation, that is, the prevailing structural conditions during the pre-COVID period. The combination of a sustained situation of globalisation, which weighed on wages and prices in developed countries, and a technological revolution that gave little room for manoeuvre in wage negotiations for low- and medium-skilled employees, helped by digitalisation and robotisation, induced the structural causes of very low inflation, perhaps around 1%. The efforts of central banks, seeking to stimulate the economy and inflation, then succeeded in increasing the growth rate, but not the level of inflation. And, in its search for an inflation target that is probably unattainable as well as with the help of a compass – the natural interest rate – that is very imprecise and conceptually questionable, monetary policy has persisted in using quantitative easing, even though GDP and credits had returned to a favorable trend. The consequence has been interest rates that have been too low for too long, that is to say, sustainably lower than growth rates. With, as a result, the rise of financial instability due to a strong growth in the indebtedness of private and public agents (in relation to GDP) and in a feedback loop with this increase in indebtedness and the very rapid and very strong rise in the value of stocks and real estate. Indeed, with long-term interest rates lower than the nominal growth rate, private and public players were encouraged to painlessly increase their debts, thus weakening their balance sheet.

And savers, or their asset managers, their pension funds or savings funds, like their life insurers, have sought to obtain a sufficient return. They have thus been encouraged to buy increasingly risky assets (drastically lowering risk premiums), increasingly long-term assets (thus taking on more and more liquidity risks), etc. The balance sheets of many economic players have thus become fragile both on the assets and liabilities side.

Furthermore, very accommodative monetary policies that persist for too long de facto increase wealth inequalities, further enriching those who already have some, and making real estate and the stock market less accessible to others. Finally, with all these effects combined, it is reasonable to think that they have ultimately contributed to the slowdown, to the languishing of the economy, by having notably allowed the development of “zombie” companies (which, with normal interest rates, would have experienced negative results).

This overall poor allocation of capital has very probably contributed to decreasing productivity gains. Furthermore, interest rates that are too low for too long may have, as in Germany for example, contributed to the rise in savings rates and not to their decline, contrary to the precepts of standard economic theory. A population with a declining demographic may indeed want to save more to prepare for its retirement, no longer being able to count sufficiently on the return on its “normal” savings. The high level of indebtedness of many players also sooner or later weighs on their investment capacity. All of these factors then lead to a structural slowdown in growth and not its support .

To conclude, it is difficult to exit quantitative easing policies once they have been used for too long. Thus the policies have developed asymmetrical characteristics which could be worrying. Among other things, this asymmetry can provide markets with free options to protect them on the downside while allowing them to play the upside with very limited risk. The consequent fragility accentuated in the financial structures of agents, both in the assets of balance sheets, which include highly valued or overval ued stocks and real estate, and in their liabilities, which have levels of debt to GDP rarely reached, rightly enco urages central banks to be very cautious in their balance sheet reduction (“quantitative tightening”). Reducing the balance sheet of issuing institutions too quickly or too intensely could indeed lead to major financial and economic crises. This is why we can consider that liquidity in central bank money will only be withdrawn – as at present – very cautiously. In fact, very probably, the opposite path will never fully reach its end. Furtherm ore, we are in an unprecedented realm since the experience of “quantitative tightening” is a historical first. The fight against the sudden return of inflation these last years has been successful thanks to conventional monetary policy effects (raising their pol icy rates) , without acting discretionarily on their balance sheet size, but driving their l ow-key reduction.

Ultimately, it seems that we can affirm, based on a retrospective analysis, that quantitative easing policies have very favorable effects when it comes to healing a violent financial and economic crisis by trying to contain systemic risk, that is to say, to prevent a catastrophic chain of events. However, if it is also useful to use them to stimulate growth and inflation, if we continue to use them, even when growth has returned, and, moreover, if the target inflation no longer corresponds to structural inflation, this may seem to entail more dangers than benefits. We have not yet seen all the economic and financial consequences that such a policy pursued for too long can induce. Let us bet that, barring new violent crises, and across cycles, central banks will seek to sustainably maintain interest rates at levels roughly equal to nominal growth rates. All things considered, and in order to be able to use it again in case of proven need, the unconventional monetary policy should remain unconventional.

Olivier Klein

Chief Executive Officer Lazard Frères Banque Professor of Economics and Finance at HEC

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Exiting the ECB’s highly accommodating monetary policy : stakes and challenges – Le Blog Note d’Olivier Klein Revue d’Economie Financière – https://www.oklein.fr/en/exiting-the-ecbs-highly-accomodating-monetary-policy-stakes- and-challenges-2/

HOW CAN WE AVOID THE DEBT TRAP AFTER THE PANDEMIC? – Le Blog Note d’Olivier

KLEIN Revue d’Economie Financière – https://www.oklein.fr/en/how-can-we-avoid-the-debt-trap-after-the-pandemic/

The benefits and costs of asset purchases ECB – https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2024/html/ ecb.sp240528~a4f151497d.en.html

Central Banks’ Exit from the Garden of Eden | Banque de France – https://www.banque-france.fr/en/governors-interventions/central-banks-exit-garden-eden