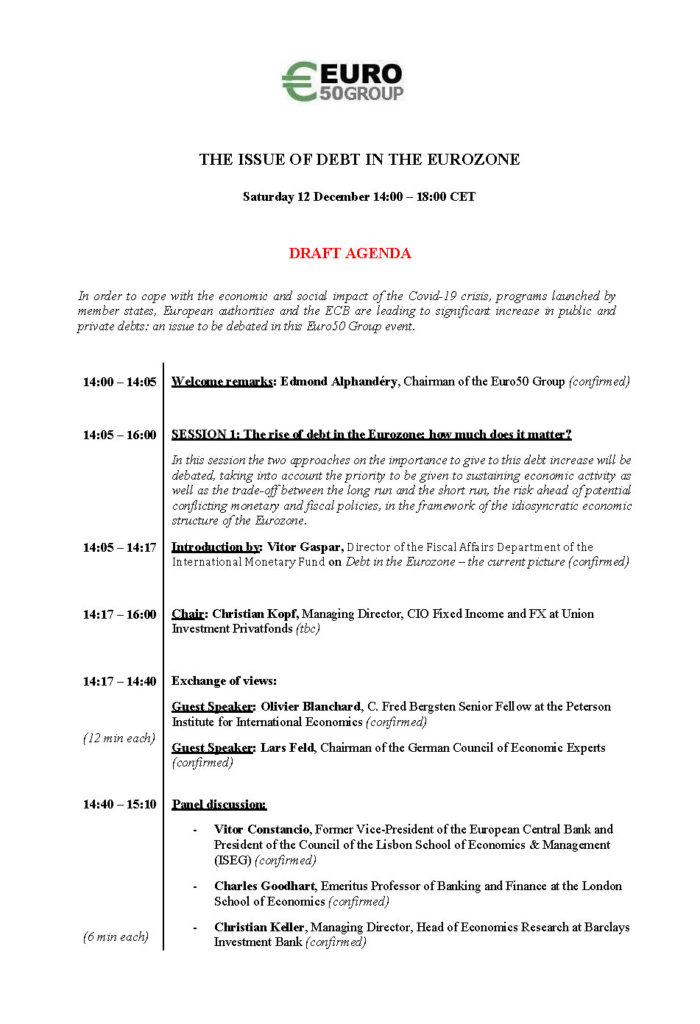

First, I am very grateful to Euro 50 for this invitation to debate the issue of debt in the Europe.

We all know that the fiscal and monetary policies currently in force are essential to limit the damage caused by the pandemic. And everything that governments and central banks have undertaken was absolutely necessary. We also know that it would be a serious mistake to drop our guard too quickly.

But, given the huge size of the debt generated by the crisis, coming on the back of a widespread increase in debt over at least 20 years, should we not be concerned about what is likely to happen when the health situation and growth return to normal? Should we not be worried about debt?

The non-repayment of public debt to private creditors would have significant consequences for the economy and for society, with a catastrophic impact on household savings and pensions. Clearly this is not a viable option. And not repaying the public debt to the central bank alone, even if this were possible, would be playing a zero-sum game insofar as the shareholders of central banks are States, so the situation must therefore be analysed in a consolidated manner.

One could possibly imagine that only the additional debt resulting from the pandemic would be refinanced at very long maturities by the central bank. But can we envisage this option being extended to future increases in public debt?

How, therefore, do we avoid succumbing to the allure of “magic money”? Particularly as during the pandemic we have ultimately found the financial resources needed to fund what previously seemed impossible. Under these conditions, it could appear to some that there is no reason not to continue down this road.

But a policy of quantitative easing with no end in sight would not work and must be avoided at all costs. Allowing the state to spend without limits and private agents to amass debt indefinitely with no constraints would have major consequences on the financial instability thus caused. With the return to a more normal rate of economic growth, keeping interest rates too low for too long would encourage or even trigger financial cycles. This would lead to even bigger speculative bubbles which, sooner or later, would inevitably burst. These well-known phenomena are the causes of major financial, economic and social crises. This point is key. In recent decades, every time that interest rates have remained too low for too long, we have seen inflation in the price of financial and/or real estate assets, with no inflation in the price of goods and services. This is because globalisation and the digital revolution have not allowed wages and prices to rise.

Finally, over the longer term, we could end up seeing a flight from money. The absence of a payment constraint, i.e. a monetary constraint, due to a policy of quantitative easing that is too strong and continues for too long, allowing debts to be financed over the long term without constraint, could give rise to a crisis of confidence in the “official” currencies insofar as the monetary system is essentially a system for settling debts, providing consistency for trade. The effectiveness of the economy depends on this. In fact, the only companies that are likely to survive over the medium and long term are those that do not incur continuous losses. Failing that, economic effectiveness would be impossible, and no Schumpeterian growth would be conceivable. The same applies to households, which cannot spend more than they earn on a lasting basis.

The entire system depends on this trust. In essence, trust is the ability to rely on someone’s word or on a signed agreement. In this case, agreements for debts and receivables, on which the whole system is based, must be respected. Trust in the banks themselves is also essential. So is trust in central banks. This is a key point, as central banks are responsible for monetary regulation, i.e. confidence in money, which is the keystone that holds the whole economic system together. If they were to issue too much central bank money for too long and without limits, a major crisis could occur, comparable to the collapse of the assignat during the French Revolution or hyperinflation during the Weimar Republic. Beyond an unspecified threshold, the national or regional currency may be rejected. This situation would lead to the disintegration of the debts and receivables system and, consequently, the potential disintegration of our whole society. This trust must be protected, or there is a risk of flight to a foreign currency. And even if all central banks acted in the same way at the same time, it would be possible to find a safe haven in gold, physical assets such as real estate, or a cryptocurrency issued someday by one of the GAFA companies that has become more solvent than the governments themselves.

Currency is an institution and must be managed as such. It must be based on trust and respect for the rules that are the alpha and omega of solid institutions. Insofar as debts undertaken by companies and governments are generally repaid by the issue of new debts, the monetary constraint is therefore based on the obligation to maintain a sustainable debt trajectory. Keeping interest rates at extremely low levels will not on its own be enough to guarantee this necessary sustainability, firstly because there is no long-term guarantee that interest rates will never rise again. Fears about future inflation already show this. But also because central banks will eventually stop buying any new debt issues and the financial markets will not step in to take their place, if the solvency trajectory is not realistic.

It is therefore possible to temporarily suspend monetary constraints, as is currently the case, but this cannot go on forever.

The legitimacy of the central banks depends on their ability to rise above private and public sector interests. In other words, making sure they protect themselves against any domination by governments or by the financial markets. Ultimately, it is the central banks’ duty to defend the public interest and preserve their credibility. Otherwise, they will not be able to maintain an efficient economic system and confidence in the currency, nor will they be able to use expansionary monetary policy in a meaningful way if it becomes necessary again. This is how they contribute to the common good and to the preservation of the social order itself. Governments and central banks will therefore quite quickly need to announce their commitment, when the time comes, to resuming fiscal, structural and monetary policies that give rise to credible trajectories.

Thank you.